Guest editorial by: Gregory L. Shelton, Horack, Talley, Pharr & Lowndes, P.A.

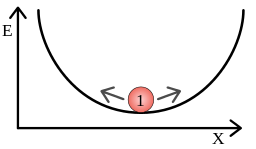

We attorneys often hammer home the importance of reviewing and negotiating solid construction contracts. Standard industry contracts offered by ConsensusDOCS, the American Institute of Architects, the Design Build Institute of America, and others, provide a good foundation for negotiations because they are reasonably fair and generally do a good job allocating risk to the party in the best position to reduce or eliminate the risk. Allocating risk in this manner comports with our innate view of fairness and is consistent with how we view the parties’ respective roles. Regard this as the natural state of contractual equilibrium.

One-Sided Construction Contracts

Some companies, particularly large owners and contractors, prefer to use their own customized agreements. In some cases, the temptation is too great, and the customized agreement becomes so one-sided that seemingly advantageous terms become counterproductive.

Before discussing the practical limits of these Darth Vader agreements, it is both wise and prudent to assume that contract terms are enforceable, even if they are so over-the-top as to induce involuntary laughter. Judges consistently tell us in their written opinions that it is not the role of the court to rewrite contracts. The North Carolina Court of Appeals put it this way: “People should be entitled to contract on their own terms without the indulgence of paternalism by courts in the alleviation of one side or another from the effects of a bad bargain.”

In other words, courts will not save you from yourself. You may have desperately needed the work. You may have been told that the written contract was just a formality for the lawyers. You may have been told “nawww, we just put that in the file cabinet and never look at it again.” But once a problem arises, the first thing we lawyers do is ask for a copy of the written contract. Words do matter; thus my entreats to clients to read the contract, or let me read the contract, before signing it or starting work.

Their Limitations

Now that I have given you fair warning about the dangers of written contracts, I am now comfortable stating my thesis:

There are practical limits to unbalanced contracts because there are legal, business, and human forces pulling the relationship toward a state of equilibrium. Further, as contracts become increasingly one-sided, so too they become increasingly unstable and unpredictable.

Legal Constraints

Some contract terms are simply dead on arrival. The legislatures in North Carolina and South Carolina have enacted statutes rendering some common contract terms unenforceable. For example, both states have enacted prompt payment acts and have enacted statutes rendering pay-if-paid clauses unenforceable. The legislatures have also enacted “anti-indemnity” statutes limiting the scope of indemnity clauses in the construction realm.

Courts have created their own rules limiting the enforceability of contract terms. A liquidated damages clause which does not reasonably estimate actual damages suffered as a result of delay will be construed by the court as an unenforceable penalty. Also, courts will disregard strict notice provisions or written change order requirements under certain circumstances. Courts can also refuse to enforce contracts that it deems illusory or unconscionable.

An unfair or unenforceable provision may threaten the entire contract. A particularly striking example of this occurred in Jackson v. Associated Scaffolders and Equipment Company, Inc., 152 N.C. App. 687 (2002), where the North Carolina Court of Appeals ruled that an unenforceable indemnity provision was not severable from the contract, and proceeded to strike the contract in its entirety.

Finally, contracts can be so unbalanced that they become susceptible to a form of legal Aikido, whereby overly aggressive provisions can be used against the drafter. With some imagination and disciplined analysis, the unbalanced contract can flipped on its back.

Business Constraints

I refuse to join any club that would have me as a member. -Groucho Marx

For the owner hiring a contractor, or a contractor hiring a sub, the success of the project depends upon the competence, integrity, and skill of those actually performing the work. Do you really want to hire someone who will sign a contract appointing your own vice president of operations as arbitrator in the event of a dispute? Or agreeing to pay half the contract balance as liquidated damages upon asserting a defense to your claim in court? Or granting you sole and unfettered discretion to determine the price of change orders?

How strapped for cash must a party be to sign away such rights? One the other side of the equation, having the legal right to rake a desperate or unsophisticated subcontractor over the legal coals isn’t worth all that much when the project blows up.

All too often, decision makers at reputable and established companies tell me that they will not bid certain work because the other party’s contract is ridiculously one-sided and offered on a “take it or leave it” basis. Market forces at work.

Human Constraints

The party seeking rigid enforcement of a brutal contract must overcome the innate sense of fairness rooted in most decision makers. People like Hobbits, not Orcs. One need look no further than landmark decisions by the U.S. Supreme Court for evidence of judges finding a way to reach a desired result. Arbitrators have even more flexibility in deciding a winner.

Merely relying on sympathy or playing the victim is a double-edged sword. From Teddy Roosevelt’s Nobel lecture: “We despise and abhor the bully, the brawler, the oppressor, whether in private or public life, but we despise no less the coward and the voluptuary. No man is worth calling a man who will not fight rather than submit to infamy or see those that are dear to him suffer wrong.” Today, you’ll likely hear this sentiment expressed as: “Well, if he’s dumb enough to sign it, its his problem.”

Conclusion

Negotiating within a few standard deviations of the fairness bell curve is good business practice. At some point, however, the drafter will encounter diminishing returns due to the opposing forces identified above. Finally, an overly onerous or one-sided contract can actually work against or turn on its creator. Read More.